advanced-js-reading-notes

Event loop

Function call stack: The function stack is a function that keeps track of all other into an error in JavaScript. That is nothing but a snapshot of the function stack at that point when the error occurred.

The event loop is the secret by which JavaScript gives us an illusion of being multithreaded even though it is single-threaded. The below illusion demonstrates the functioning of the event loop well: Here the callback function in the event queue has not yet run and is waiting for its time into the stack when the SetTimeOut () is being executed and the Web API is making the mentioned wait. When the function stack becomes empty, the function gets loaded onto the stack as shown below: That is where the event loop comes into the picture, it takes the first event from the Event Queue and places it onto the stack i.e in this case the callback function. From here, this function executes calling other functions inside it, if any. This cycle is called the event loop and this is how JavaScript manages its events.

Memory allocation in JavaScript:

1. Heap memory: Data stored randomly and memory allocated.

2. Stack memory: Memory allocated in the form of stacks. Mainly used for functions.

you can watch this video for more information 👈

JS callback functions

What is a Callback Function?

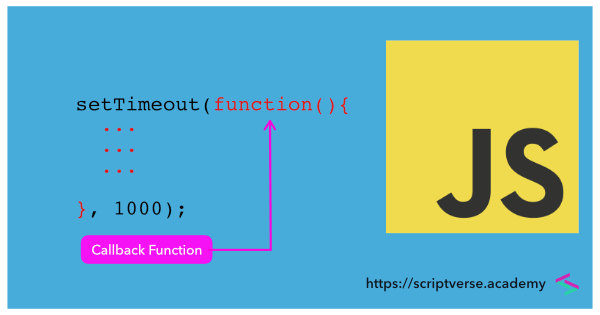

Can we pass objects to functions as parameters? So, we can also pass functions as parameters to other functions and call them inside the outer functions. Let me show that in an example below:function print(callback) { callback();}The print( ) function takes another function as a parameter and calls it inside. So a function that is passed to another function as a parameter is a callback function. You can also watch the video version of callback functions below:

Why do we need Callback Functions?

JavaScript runs code sequentially in top-down order. However, there are some cases that code runs (or must run) after something else happens and also not sequentially. Callbacks make sure that a function is not going to run before a task is completed but will run right after the task has completed. It helps us develop asynchronous JavaScript code and keeps us safe from problems and errors. In JavaScript, the way to create a callback function is to pass it as a parameter to another function, and then to call it back right after something has happened or some task is completed.

How to create a Callback

To understand what I’ve explained above, let me start with a simple example. We want to log a message to the console but it should be there after 3 seconds.const message = function() { console.log(“This message is shown after 3 seconds”);} setTimeout(message, 3000);There is a built-in method in JavaScript called “setTimeout”, which calls a function or evaluates an expression after a given period of time (in milliseconds). So here, the “message” function is being called after 3 seconds have passed. ( 1 second = 1000 milliseconds)In other words, the message function is being called after something happened (after 3 seconds passed for this example), but not before. So the message function is an example of a callback function.

Callback as an Anonymous Function

Alternatively, we can define a function directly inside another function, instead of calling it. It will look like this:setTimeout(function() { console.log(“This message is shown after 3 seconds”);}, 3000);As we can see, the callback function here has no name and a function definition without a name in JavaScript is called as an “anonymous function”. This does exactly the same task as the example above.

Callback as an Arrow Function

If you prefer, you can also write the same callback function as an ES6 arrow function, which is a newer type of function in JavaScript:setTimeout(() => { console.log(“This message is shown after 3 seconds”);}, 3000);

What about Events?

JavaScript is an event-driven programming language. We also use callback functions for event declarations. For example, let’s say we want users to click on a button:</button id=”callback-btn”>Click here</button/> This time we will see a message on the console only when the user clicks on the button:document.queryselector(“#callback-btn”) .addEventListener(“click”, function() { console.log(“User has clicked on the button!”);});So here we select the button first with its id, and then we add an event listener with the addEventListener method. The first one is its type, “click”, and the second parameter is a callback function, which logs the message when the button is clicked. As you can see, callback functions are also used for event declarations in JavaScript.

Callbacks are used often in JavaScript, and I hope this post helps you understand what they actually do and how to work with them easier.

you can read from here for more information 👈

JS Promises

A Promise is a proxy for a value not necessarily known when the promise is created. It allows you to associate handlers with an asynchronous action’s eventual success value or failure reason. This lets asynchronous methods return values like synchronous methods: instead of immediately returning the final value, the asynchronous method returns a promise to supply the value at some point in the future.

A Promise is in one of these states:

- pending: initial state, neither fulfilled nor rejected.

- fulfilled: meaning that the operation was completed successfully.

- rejected: meaning that the operation failed.

A pending promise can either be fulfilled with a value or rejected with a reason (error). When either of these options happens, the associated handlers queued up by a promise’s then method are called. If the promise has already been fulfilled or rejected when a corresponding handler is attached, the handler will be called, so there is no race condition between an asynchronous operation completing and its handlers being attached.

- As the Promise.prototype.then() and Promise.prototype.catch() methods return promises, they can be chained.

Benefits of Promises:

1- Improves Code Readability.

2- Better handling of asynchronous operations.

3- Better flow of control definition in asynchronous logic.

4- Better Error Handling

Parameters:

1- Promise constructor takes only one argument which is a callback function (and that callback function is also referred as anonymous function too).

2- Callback function takes two arguments, resolve and reject.

3- Perform operations inside the callback function and if everything went well then call resolve.

4-If desired operations do not go well then call reject.

you can read from here for more information 👈

JS Async/Await

Async:

It simply allows us to write promises based code as if it was synchronous and it checks that we are not breaking the execution thread. It operates asynchronously via the event-loop. Async functions will always return a value. It makes sure that a promise is returned and if it is not returned then javascript automatically wraps it in a promise which is resolved with its value.

Await:

Await function is used to wait for the promise. It could be used within the async block only. It makes the code wait until the promise returns a result. It only makes the async block wait.

you can read from here for more information 👈

Test-Driven Development

What is Testing?

Testing is the process of ensuring a program receives the correct input and generates the correct output and intended side-effects. We define these correct inputs, outputs, and side-effects with specifications. You may have seen testing files with the naming convention filename.spec.js. It is the file where we specify or assert what our code should do and then test it to verify it does it. You have two choices when it comes to testing: manual testing and automated testing.

Manual Testing

Manual testing is the process of checking your application or code from the user’s perspective. Opening up the browser or program and navigating around in an attempt to test functionality and find bugs.

Automated Testing

Automated testing, on the other hand, is writing code that checks to see if other code works. Contrary to manual testing, the specifications remain constant from test to test. The biggest advantage is being able to test many things much faster. It’s the combination of these two testing techniques that will flush out as many bugs and unintended side-effects as possible, and ensure your program does what you say it will. The focus of this article is on automated testing, and in particular, unit testing. E2E tests test an application as a whole.

Recap:

Testing is verifying our application does what it should. There are two types of tests: manual and automatedTests assert that your program will behave a certain way. Then the test itself proves or disproves that assertion.

Test-Driven Development:

Test-driven development is the act of first deciding what you want your program to do (the specifications), formulating a failing test, then writing the code to make that test pass. It is most often associated with automated testing. Although you could apply the principals to manual testing as well. Traditionally, we would make a table, then once the table is made, test it to make sure it does, well, what a table should do. The test passes.I expect the table to hold a 20-pound object. I move the one leg to the outer edge of the table and add two more legs to create a tripod structure.

Recap

With TDD, test logic precedes application logic.

A Practical Example

Imagine we have a program that manages users and their blog posts. We need a way to keep track of the posts a user writes in our database with more precision. Right now, the user is an object with a name and email property:user = { name: ‘John Smith’, email: ‘js@somePretendEmail.com’ }We will track the posts a user creates in the same user object.user = { name: ‘John Smith’, email: ‘js@someFakeEmailServer.com’ posts: [Array Of Posts] // <—–}Each post has a title and content. Instead of storing the entire post with each user, we’d like to store something unique that could be used to reference the post. We first thought we would store the title.

Set up our testing environment

Often, you’ll need a testing library and a separate assertion library, but Jest is an all-in-one solution. An assertion library allows us to make assertions about our code. So in our wooden table example, our assertion is: “I expect the table to hold a 20-pound object.” In other words, I am asserting something about what the table should do.

Project setup

| Create id.js and add it to the project’s root. We are approaching this purely from a unit-testing standpoint. In the command line, run our test script: npm run test. testMatch: /__tests__//.js?(x),**/?(.)+(spec | test).js?(x) - 0 matches testPathIgnorePatterns: /node_modules/ - 3 matchesJest is looking for a file name with some specific characteristics such as a .spec or .test contained within the file name. A little bit better, it found the file, but not a test. |

How Do We Write a Test?

Tests are just functions that receive a couple of arguments. Let’s analyze the test and results output. Although, in this case, we aren’t asserting something about our code, but rather something truthy in general that will pass, a sort of sanity check….() => { expect(1).toBe(1) });This assertion is mathematically true, so it’s a simple test to ensure we’ve wired up Jest correctly. The results tell us whether the test passes or fails. It also tells us the number of tests and test suites.

A side note about organizing our tests There is another way we could organize our code. Or even a couple of describes–maybe one for each file we are testing. For our purposes, we will just focus on test and keep the files fairly simple.

Testing Based on Specifications As tempting as it is to just sit down and start typing application logic, a well-formulated plan will make development easier. We need to define what our program will do. We define these goals with specifications. For our small project we will use the following specifications:Create a random numberThe number is an integer. The number created is within a specified range.

Recap Jest is a testing suite and has a built-in assertion library. A test is just a function whose arguments define the test. Specifications define what our code should do and are ultimately what we test.

Specification 1- Create a Random Number

JavaScript has a built-in function to create random numbers–Math.random(). What we want to do is use math.random() to create a number and then ensure that is the number that gets returned. Isn’t the point to test the real code? Many functions contain things we cannot control, for example an HTTP request. And, in the event those are dependencies we’ve written, we will likely write separate tests for them. Math = mockMath; const id = getNewId(); expect(id).toBe(0.75);});

Breaking the above test down Then we change the random method to return a constant value, something we can expect. Finally, we replace the global Math object with our mocked Math object. However, I wanted to show you this method, since there will be times that a Jest-mocked function will be required for other functionality in our tests to work .Run the test: npm run testFAIL ./id.spec.js✕ returns a random number (4ms)● returns a random number ReferenceError: getNewId is not definedNotice we get a reference error just like we should. Normally, the test would be written in a separate file, with any dependencies imported as they are needed. Ideally, we want to get to our assertion errors as quickly as possible.

Specification 2- The number we return is an integer.

Math.random() generates a number between 0 and 1 (not inclusive). In fact, we are creating a real value as well since we are returning a number between 0 and 1 (not inclusive). FAIL ./id.spec.js✓ returns a random number (1ms)✕ returns an integer (4ms)● returns an integerexpect(received).toBe(expected) // Object.is equalityExpected: 0Received: 0.75Wow, what are the chances this function just happened to return the mocked value! Math); mockMath.random = () => 0.75; global. Although, that is somewhat meaningless, because we could call Math.random()anywhere in our code, never use it, and the test still passes. We’ve already seen how to mock a function, so here we spy on Math.floor().

Specification 3: The number is within a specified range.

We know Math.random() returns a random number between 0 and 1 (not inclusive). However, we actually call it with 0.75 plus and minus a max and min value that isn’t yet defined. Here we will re-write the first test to include some of our new knowledge.test(‘returns a random number’, () => { jest.spyOn(Math, ‘floor’); const mockMath = Object.create(global. We can do this because we know if Math.random() gets called, the value is set to 0.75. We only generated a single random number. What are the chances that number just happened to be in the range and pass the test?Fortunately here, we can mathematically prove our code works.

Is it ok to use multiple assertions in one test?

That isn’t to say you shouldn’t attempt to reduce those multiple assertions to a single assertion that is more robust. For example, we could rewrite our test to be more robust and reduce our assertions to just one.test(‘generates a number within a defined range’, () => { const min = 10; const max = 100; const range = []; for (let i = min; i < max+1; i ++) { range.push(i); } for (let i = 0; i < 100; i ++) { const id = getRandomId(min, max); expect(range).toContain(id); }});Here, we created an array that contains all the numbers in our range. We then check to see if the ID is in the array.

Specification 4: The number is unique

First, we need to define what unique to us means. Most likely, somewhere in our application, we would have access to all ID’s being used already. Our test should assert that the number that is generated is not in the list of current IDs. There are a few different ways to solve this. We could use the .not.toContain() we saw earlier, or we could use something with index.

indexOf()

test(‘generates a unique number’, () => { const id = getRandomId(); const index = currentIds.indexOf(id); expect(index).toBe(-1);});array.indexOf() returns the position in the array of the element you pass in. So, what happened?Again, we are getting lucky. What we could do is check to see that our getNewId() function could somehow be self-aware when a number is or is not unique. In the second example, we constrain it in a way where it should only be able to return 6.FAIL ./id.spec.js✓ returns a random number (1ms)✓ returns an integer (1ms)✓ generates a number within a defined range (24ms)✕ generates a unique number (6ms)● generates a unique numberexpect(received).toBe(expected) // Object.is equalityExpected: “failed”Received: 1Our test fails. Second, we use a do-while loop since we don’t know how many times it will take to create a random number that is unique. However, we still want to make sure the last number we created doesn’t pass the unique test.

Some of what we did was for demonstration purposes. Testing whether our number was within a specified range is fun, but that formula can be mathematically proven. Ultimately, test-driven development provides us with a framework to think about our code at a more granular level. It is up to you, the developer, to determine how granular you should define your tests and assertions. This might cause a reluctance to refactor because now you must also update your tests.